Mount Lamington

1951

On Sunday January 21, 1951, Mount Lamington erupted.

Essential to village life, the multi-peaked volcano had until then been a rich hunting ground and source food.

Many even believed Mount Lamington held supernatural powers.

Few could’ve predicted the destructive power lurking beneath.

On that day in 1951, thousands died.

Some survived.

These are their stories.

Counting down to Eruption Day

Day 1 Monday, 15 January

Six days before the eruption, landslide scars on the inner faces of the peaks were observed by several people. A cook at the Sangara Rubber Plantation also reported seeing “white vapour” rising from Mount Lamington’s peaks. For many locals, this was interpreted as being a bad omen.

Angela Arasepa

10-years-old

Survivor

“I was in the village with my parents (before eruption day). We didn’t know anything. We just stayed (at home). Something was happening, we (just) didn’t know what.”

Roderick Orari

13-years-old

Survivor

“We didn’t worry about Mount Lamington because that’s the first time in history (it had erupted). The word volcano was new to my parents and (to) everyone.”

Day 2 Tuesday, 16 January

Tremors and unrest continued through Tuesday. For the first time a vapour column had become easily visible from the village of Higaturu. By late afternoon that day, Higaturu residents also reported seeing more landslides down the slopes of Mount Lamington.

Angela Arasepa

10-years-old

Survivor

“We didn’t know the volcano (had) started. We (heard and felt) the earthquake and the thunder. (There was a) big storm.”

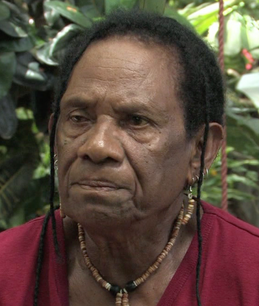

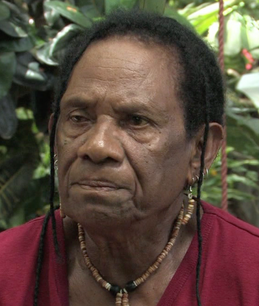

John Javiripa

Age unknown

Survivor

“When they saw the smoke, they didn’t have any idea as to what was going to happen. It was the first time ever to see such smoke, because it was dormant all this time. And as soon as they saw the smoke, they never had a clue. They were confused as to what was happening.”

Procoholus Korina

8-years-old

Survivor

“It’s the first time (this community) saw this sort of thing happen. So most of the community, they were not scared. They don’t know what was going to happen.”

Day 3 Wedmesday, 17 January

Cloud cover slowly cleared by 10:30am on Wednesday, revealing a spiral of dark gray ash and smoke rising from a valley between surrounding hills and Mount Lamington. Ground tremors and volcanic emissions increased in density and intensity throughout the day, resulting in a big storm that night.

Mary Gole

9-years-old

Survivor

“(There was a) big like thundering earthquake. Very big noise that night.”

Father Franklin Otoha

24*years-old

Survivor

“Things were happening on the 17th of January, that is a Wednesday. Ver, very big smoke came up from the mountain. I had my brothers with me. And we don’t know what (was happening) but something (was) happening there.”

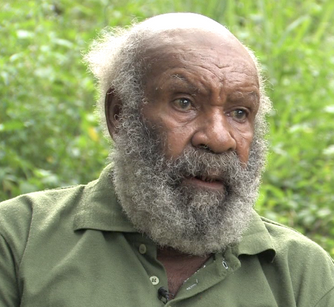

Maclaren Hiari OL MBE

Historian

“It was rumbling and smoking for four days prior to the big explosion. And people were not moved by it. But you know they never thought that the mountain would explode.”

Day 4 Thursday, 18 January

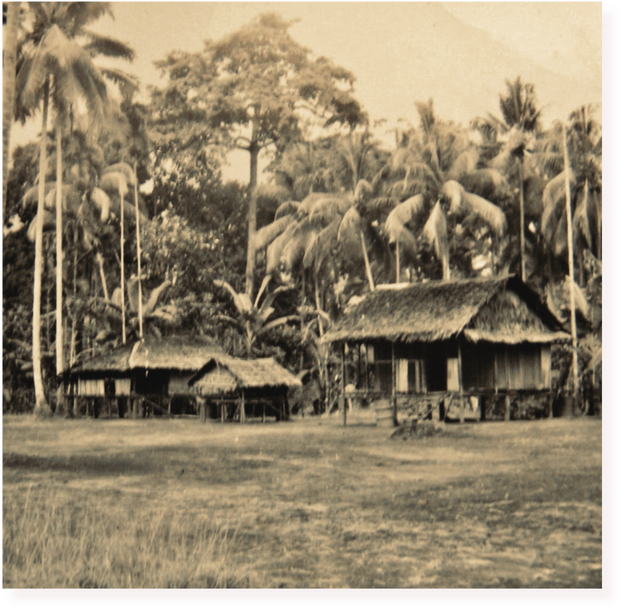

Picture taken by Kevin Woiwod in Higaturu, on 18 January.

In the early hours of Thursday morning residents reported hearing a deafening roar from Mount Lamington.

District Commissioner at the time, Cecil Cowley, observed a thick black ash and smoke column billowing from a nearby hill.

Throughout the day the volcanic emissions increased, the smoke colour ranging from black to gray. All the while, earthquakes shook the Higaturu region with almost non-stop frequency.

At this point, many had become alarmed at Mount Lamington’s near constant activity.

It had also caught the attention of residents in the nearby Isivita and Waseta villages.

At the Eroro Mission on the north coast, residents were rocked by the sound of a large explosion followeed by an emerging cloud of thick black smoke high over Mount Lamington. Residents of the mission climbed to the top of their homes to get a better view, before it was concluded that a fuel drum must have exploded over at Higaturu.

In the early afternoon of that day, District Commissioner Cowley sent the following radiogram from Higaturu to the Department of District Services and Native Affairs in Port Moresby:

CONTINUOUS EARTH TREMORS COMMENCING EVENING 16TH AVERAGE SEVENTY PER DAY STOP LAMINGTON COMMENCED ERUPTING 11 OCLOCK THIS MORNING 18TH STOP SIX SPIRALS VERTICAL STOP LANDSLIDES PLENTIFUL IN VIEW ALSO STREAM FLOWING DOWN STEEP RAVINE SAND COLOURED STOP DIFFICULT DETERMINE EARTH WATER OR LAVA STOP VAST SMOKE BILLOWING WHOLE NORTHERN MOUNTAINSIDE 2 PM STOP ESTIMATED DISTANCE FROM HIGATURU EIGHT MILES STOP CONSIDER NO NEED ALARM BUT YOU MAY CARE INVESTIGATE BY AIRCRAFT STOP WILL KEEP YOU INFORMED STOP SUGGEST RADIO CONVERSATION 4.30 PM TODAY.

Day 5 Friday, 19 January

After days of violent earth tremors, Friday started with observations of a light-coloured ash covering the summit peaks of Mount Lamington.

While District Commissioner Cowley had requested a volcanologist, Acting Administrator Judge Phillips arrived at Popondetta after conducting an aerial inspection of Mount Lamington.

Judge Phillips later recorded his impressions:

“It was not moving violently at all, but rising so gently and slowly that one had to look at it for an appreciable time to detect movement ... it was not spasmodic and did not emerge in violent bursts: in short, it looked as if the initial force of the volcano had spent itself and as if the forces underneath had found sufficient outlet. The appearance of that column reminded me of that of the column from the volcano that erupted at Vulcan Island at Rabaul in 1937, several days after the actual eruption, when the Vulcan column was beginning gradually to subside.” (Deputy Administrator 1951, 5)

Judge Phillips noted the anxiousness of the ladies present at the Popondetta airstrip, but he “...did not think an immediate evacuation was necessary”.

Judge Phillips and his wife left for Port Moresby shortly after.

Later that day however, conditions on Mount Lamington deteriorated.

Day 6 Saturday, 20 January

The day started clear, allowing many observations to be made of the escalating volcanic activity. The active area in the old crater had enlarged, and there were, according to witness, as many as four or five active vents. Rodd Hart had been working as a mechanic in Jegarata village - the small community was directly facing the open crater. He reported that the sounds emerging from the mountain for three days were like those of a ‘gigantic underground railway’.

For the wife of District Commissioner Cowley - Amalya Cowley - the constant rumblings and tremors had caused sleepless night at her Higaturu home. Mrs. Cowley was encouraged by her husband to spend the night at the nearby Sangara Rubber Plantation. Mrs. Cowley reluctantly agreed and departed Higaturu with her daughter Pamela.

That night, the number of earthquakes felt not only decreased in frequency after about 8:00pm, but some say they appeared to have ceased almost altogether by Sunday morning.

Father Franklin Otoha

24-years-old

Survivor

“(On Saturday we went up to Higaturu to play cricket with the government workers. (District Commissioner) Mr. Cowley said ‘no sorry, you people can’t play. The time is no good. You must go back to your place.”

Eruption Day

Sunday, January 21, 1951

The day started like any other Sunday.

Families went to church.

The village children were making the most of their remaining school holidays.

It was life as usual until around 10:00am.

Survival and Aftermath

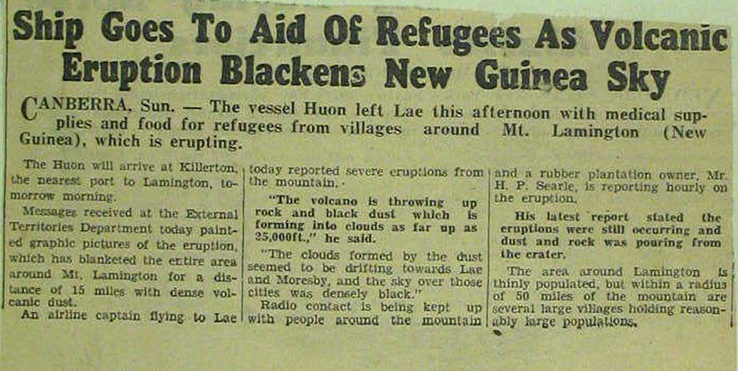

The eruption of Mount Lamington destroyed the District Headquarters and claimed the lives of all the administration staff and many of the local Orokaivans. Assistance and hospitalization of the injured were the first consideration. Assistance was flown from Port Moresby and Buna and ships were sent with food and medical supplies. Temporary tented hospitals and accommodation were established at several locations, and it was decided that Popondetta was the temporary administration center.

After the thick smoke has cleared, the retrieval mission started. It revealed that the once lush food bowl and rich hunting ground had been transformed.

“The first glimpse of the utter desolation was from the air, from the plane as we were coming in. And it was clearly defined everything was destroyed. The timber trees were lifeless, stripped of all greenery. Just stark skeletons. The actual station at Higaturu, where it had been, was flattened and deserted”, said Albert Speers, a former Australian Medical Officer who was charged with helping collect what remained of the bodies. “It was a terrible task. Any reclaiming of the body they would be digging a six-foot-wide hole for only a little bag of bones.”

Mary Gole

9-years-old

Survivor

“(It was) like a desert. No coconut trees, no houses. Nothing. No garden... Just like desert.”

“I really don’t know what happened with my other sisters. They walked back or… Most of the bodies were never found. The animals, dogs and pigs ate them.”

Father Franklin Otoha

24-years-old

Survivor

“No one there, nothing. All the people died.”

In the first days after the eruption, the rescue teams had to leave the victims where they fell as there were still fears of further eruptions. They later buried them where they were found or at village cemeteries if possible. Non-Papuan victims that could be identified were taken to Popondetta. The burial and recovery and identification continued for many months.

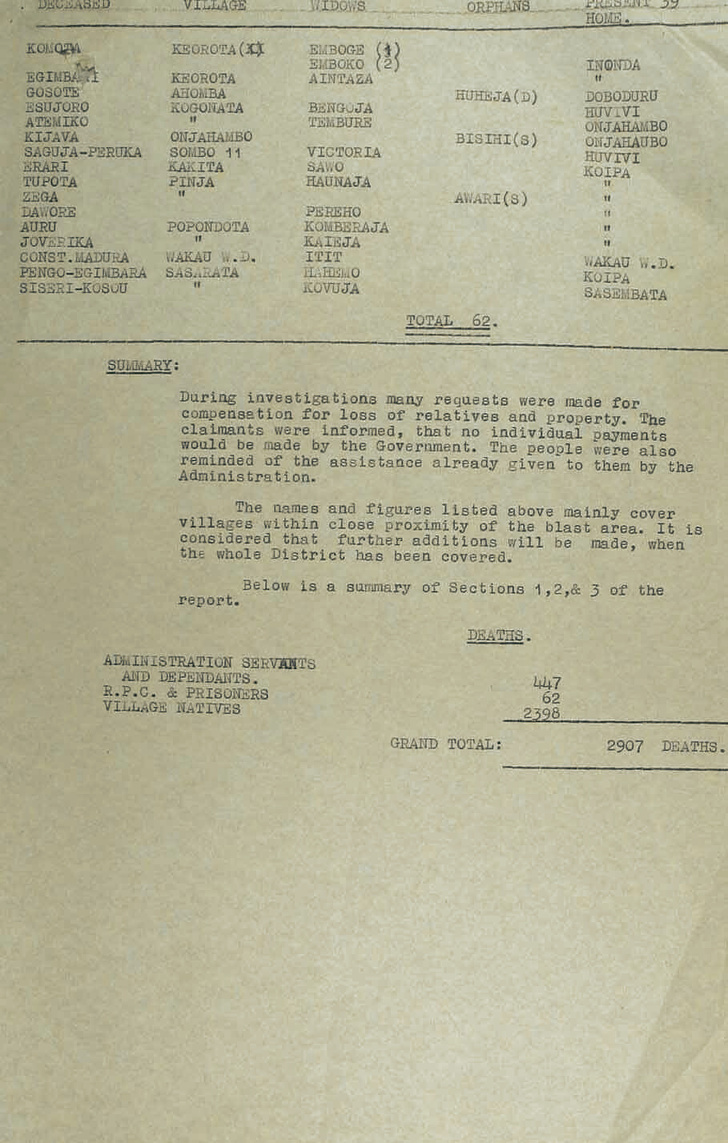

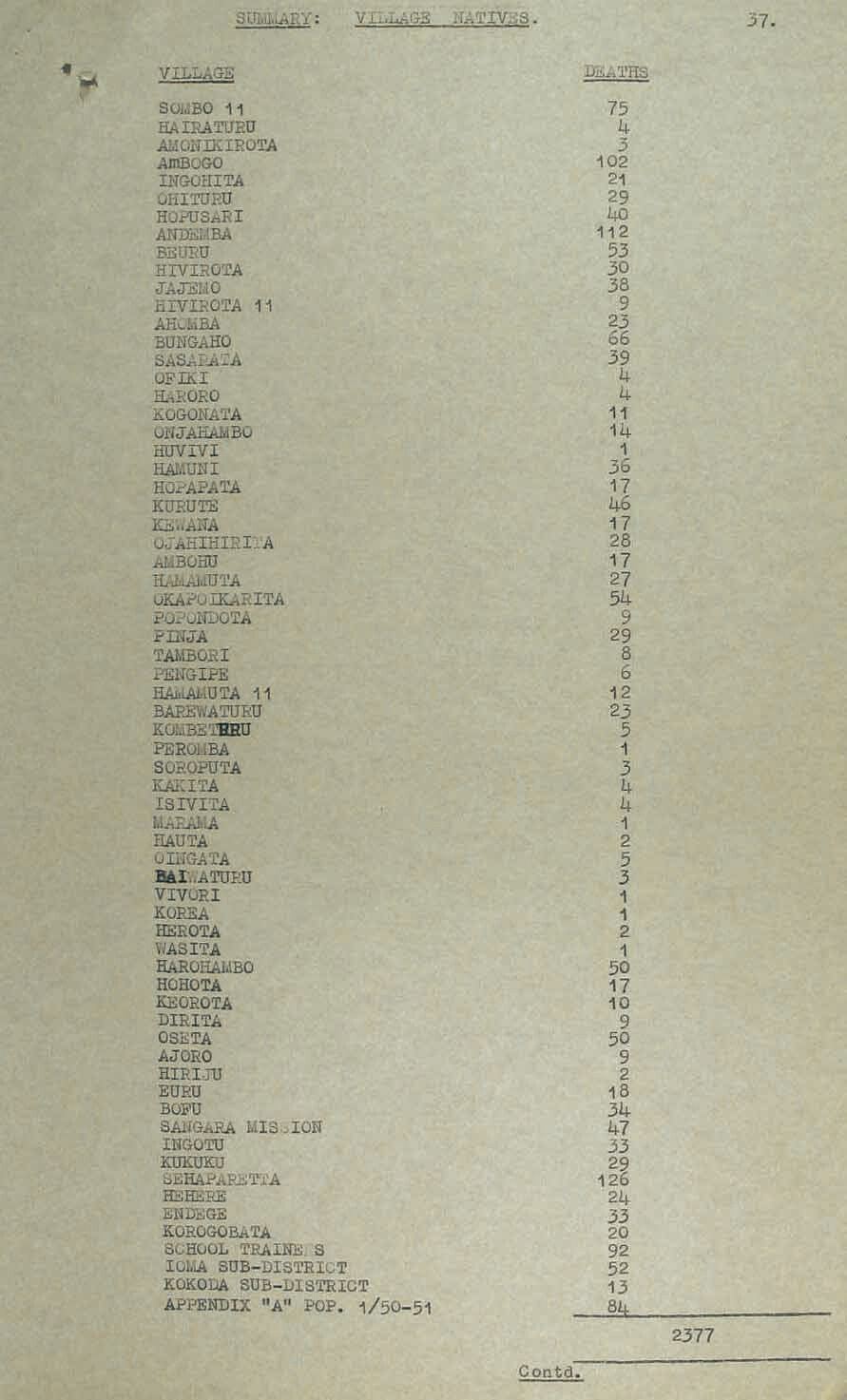

According to historian, Maclaren Hiari, the eruption affected an area of 13 by 24 kilometres and destroyed 40 villages. The official death toll stands at 2942, but the locals estimate the number to be much higher. Only 250 recognisable bodies were recovered.

Memorial Day

24th November 1952

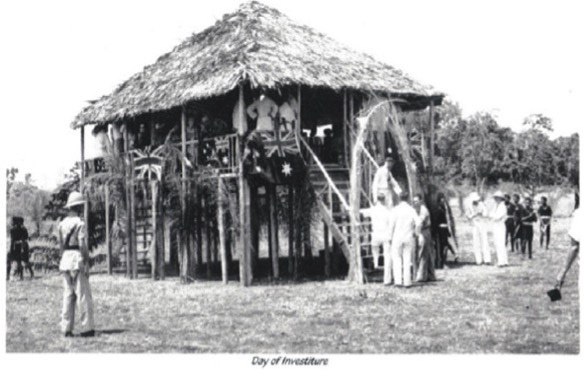

In 1952, new District Commissioner Mr. S. Elliott-Smith instructed that an area of ground at Popondetta be set aside as a cemetery and set the 24th of November 1952 for a Memorial service to be held. A plan was prepared, and the European victims were interred in graves marked with a cross.

A landscaped area with intersecting coral pathways formed a great white cross which was visible for many miles. At the centre of the white cross, raised garden beds bordered by stone formed a smaller cross. A memorial plaque was placed at the base of the central outline of the cross. The pathways of the cemetery were bordered by dwarf shrubs, and on either side are raised gardens with flowering shrubs forming the words “Memorial Cemetery”. The graves of the victims were in the two upper quarters of the cemetery in a setting of green lawn, each marked by a small white cross.

Official Party for the Memorial Day:

- The Minister for Territories. Hon. Paul Hasluck MP and Mrs Hasluck

- The Acting Administrator of Papua and New Guinea. Mr D M Cleland and Mrs Cleland

- The Anglican Bishop of New Guinea. Rt Rev P N Strong

- The District Commissioner Mr S Elliot-Smith and Mrs. Elliot-Smith

- Sub-Inspector G Allen and Mrs Allen

- The Official Secretary to the Administrator, Mr. D Sullivan

At 9:30am of 24 November 1952, the graves of the victims were consecrated by Bishop Strong and Rev. Father Conlen.

1500 Papuans of the District in ceremonial headdress and paint formed on three sides of the cemetery. A contingent of the Royal Papuan and New Guinea Constabulary lined the roadway.

Over the years, the cemetery became overgrown and neglected. Being a memorial to the non-Papuan victims, it was understandable that the local Papuans did not feel obliged to maintain the area.

In 1970, the District Commissioner at the time decided to “tidy up” the cemetery. All the white crosses and stonework were removed and replaced by a large concrete cross. The names of the European victims were engraved on small brass plates set around the sides of the cross.

The original cross from 1952.

The concrete cross lined with brass plates with the names of the European victims in 1970.

Now, more than 70 years since the eruption, the locals hold an annual memorial service.

Oro Province

Renowned for its butterflies

Oro Province, also known as the Northern Province, is a coastal province in Papua New Guinea. Situated along the coast, it shares its borders with Morobe Province, Central Province, and Milne Bay Province. The devastating eruption of Mount Lamington in 1951 resulted in significant casualties and the destruction of the district headquarters and numerous villages. As a result, Popondetta became the new capital of Oro Province.

Despite its remote location, Oro Province boasts remarkable natural beauty. Surrounded by the Owen Stanley Range and the Solomon Sea, it offers breathtaking landscapes. The province is known for being home to the world's largest butterfly and features fjord-like rias, an active volcano, and a renowned World War II battle site.

The history of Oro Province is as remarkable as its landscapes. From the gold rush to World War II and the eruption of Mount Lamington in 1951, the province's past is filled with significant events that shaped its destiny. Popondetta serves as the main town, with its main road connecting the entire province. It is a popular starting point for trekkers embarking on the challenging Kokoda Trail.

Wanigela, a coastal village with a grass airstrip dating back to World War II, played a crucial role as a supply base during the defeat of the Japanese forces at Buna. Tufi, another hidden gem within Oro Province, offers breathtaking scenery, a vibrant local culture, and exceptional diving opportunities. Kokoda, located approximately two hours from Popondetta, serves as a base for trekkers planning to undertake the famous Kokoda Trail.

The Kokoda Trail is a 96-kilometer trek that provides awe-inspiring views of the Kokoda valley and passes through significant World War II sites. It presents challenges with rugged terrain and reaches an altitude of 2,190 meters. Trekkers are advised to obtain a permit from the Kokoda Track Authority and trek with a guide and in a group for safety.

Overall, Oro Province in Papua New Guinea is a hidden gem with stunning landscapes, a rich history, and exciting adventure opportunities. From its natural wonders to its involvement in World War II, the province offers a unique and captivating experience for travellers seeking to explore its beauty and learn about its past.

Higaturu 1949 – 1951

District Headquarters at Higaturu Village 1951

Higaturu village emerged as the District Headquarters due to the Native Plantations Ordinance of 1918 and 1925-52, which promoted indigenous cash cropping. Sixteen coffee plantations were established near Mount Lamington, with a European controller based in Higaturu. The produce from these plantations was transported to Higaturu, Popondetta, and Buna for processing and shipping. However, the labor was demanding, and the scheme was deemed unsuccessful. Additionally, there was interest in developing European-managed rubber plantations in the district.

In December 1942, Captain Thomas Grahamslaw proposed Higaturu as the temporary district headquarters after the Japanese occupation. The suggestion was accepted, and administration offices were established in Higaturu, eventually becoming the permanent headquarters, replacing the previous centre in Buna due to its cooler climate.

In 1943, Chief Justice of Queensland, Sir William Webb, led a Commission of Enquiry into wartime atrocities that affected Australians. The investigation, conducted after the Japanese defeat at Buna but before full civil authority resumed in the Lamington district, examined cases of eight individuals, including four female missionaries, who were murdered by the Japanese in the Sangara-Popondetta area. The killings were classified as "atrocities" and were found to have been committed with "fiendish brutality."

Papuan trials for accusations of betrayal and Japanese sympathies were held in Higaturu. Captain W.R. 'Dickie' Humphries, an ANGAU Officer and former resident magistrate, conducted most of the proceedings. Public hangings of five Papuans occurred in the Higaturu area, followed by 17 more. The hangings were carried out on specially constructed gallows, two at a time, throughout the day, in front of a large local audience. The condemned individuals were civilians who should have been tried under Australian civil law, not military jurisdiction. However, the army wanted to assert Australian authority and didn't follow proper legal procedures. The Australian Cabinet in Canberra learned about the hangings and other events only after they had taken place.

In 1944, Dennis Taylor and his family relocated to Sangara to revive the Anglican mission. Higaturu and Sangara developed as twin settlements for State and Church representatives.

Living quarters at Higaturu 1951

The TPNG administration's postwar headquarters for the Northern Division were located at Higaturu, near the reoccupied Sangara Mission and approximately 10 kilometers from the summit of Lamington. The surrounding area had around 4,000 Sangara people, primarily engaged in subsistence agriculture, residing in villages and hamlets. Higaturu could be accessed via a short connecting track southeast from the main road between Popondetta and Wairopi, leading westwards to Kokoda.

By 1950, District Commissioner Cecil Cowley was in control of the Northern Division, with headquarters consisting of a simple single-story building and an assembly area for raising the Australian flag on special occasions. Facilities in Higaturu included a post office, hospital, doctor's residence, staff accommodation, Department of Works and Housing support, technical training center, police barracks, parade ground, and a jail. Radio communication with Port Moresby and other stations was established in Higaturu, while the nearest airstrip was in Popondetta, around 10 kilometres to the northeast and 21 kilometres from the summit of Mount Lamington. Mail services improved after the war, with small aircraft facilitating mail transport from Popondetta, unlike the pre-war era when police runners carried mail to Kokoda.

Europeans who lived in and visited the Higaturu–Sangara area commented on its impressive scenic setting: the great blue mountains of the Owen Stanley Range to the south and multi-peaked Mount Lamington in front of them. The schoolteacher, Miss de Bibra, for example, wrote that Lamington:

“Lies behind us and consists of four or five sugar-loaf peaks [that, at times, are shrouded] in gossamer scarves of mist … We have always loved her for her beauty and nearness.”

Mount Lamington was not inspected by geologists or volcanologists immediately after the war, but aerial photographs taken in 1947-48 provided valuable information. The photographs revealed that Mount Lamington was a geologically young volcano, distinguished from the older Hydrographers Range to the east. Young lava flows, in the form of bulbous "lava domes" and short stubby flows called "coulées," were observed around the summit. Another notable feature captured in the aerial photographs was an amphitheatre-like depression, serving as a summit volcanic crater. This depression faced north and was drained by the Ambogo River in the west and the Banguho River in the east, both flowing across the populated piedmont area. Erosion caused by these rivers and rock avalanches from the headwall had enlarged the amphitheater's headwall. The resulting debris was transported down what was appropriately referred to as "the avalanche valley" by Taylor (1958).

Higaturu was completely destroyed by the eruption of Mt Lamington the 21st January 1951. All residents including District Commissioner Cecil Cowley and his son Erl perished. Higaturu was not re-built and the District Headquarters moved to Popondetta.

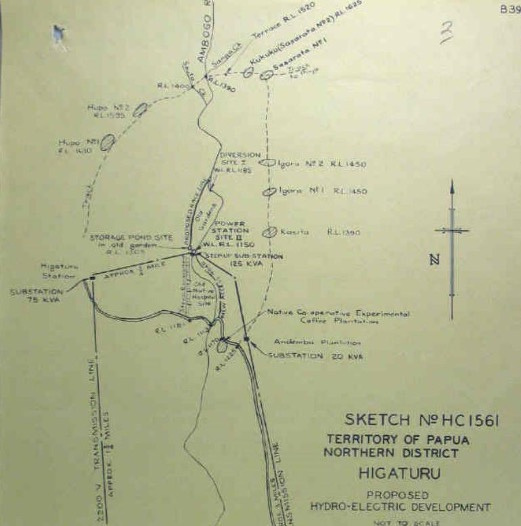

Hydro-electric plans for Higaturu

Sketch plans and photos of the proposed location of the power station on the Ambogo River

As early as 1942, after the Japanese occupation, Higaturu was proposed as a temporary District Headquarters, administrative offices were established, eventually becoming permanent. Higaturu Station was established on the site of the old Higaturu coffee plantation on the foothills of Mt Lamington. At an elevation of 1500 feet there was a panoramic view over the plains to the coast, with a serviceable road to Cape Killarton, a distance of 27 miles. It was described as very fertile countryside where agriculture flourished.

Records show that discussions on a hydro-electric development on the Ambogo River were made as early as 1948, possibly earlier but letters confirming that are not available. In a letter to the Administrator of Papua New Guinea by J Halligan in February 1950 the progress on the establishment of a hydro-electric development on the Ambogo River was discussed. The hydro-electric development would be sufficient to supply the future needs of the Higaturu and Sangara area. It was pointed out that due to the expanding agriculture there was already a need for increased power. Mention was made of turbines being available from the Snowy Mountains Authority and Scottsdale in Tasmania.

At the same time a letter from the Department of Works and Housing mentions the erection of 12 pre-cut houses for the Higaturu area. In another letter dated 24th February to Administrator Murray mentions is made of a requisition already lodged for 200 houses. Another letter undated described the future power needs. Such as European type residences for Administration 20, Sangara Rubber Estate 8, Sangara Mission 4 and 5 Trade stores buildings. Mention is also made of a 15 bedroom hotel at Sangara, a sawmill and rubber factory, 200 bed hospital, and 1000 personal in villages .Then allowances for Church, schools, offices and stores, coffee machinery Workshop and carpenters shop. It can be seen that Higaturu station was planned to become a major town and future capital of the Province and it is obvious that planning began earlier than 1948.

Power for the Hydro-electric would come from the Ambogo River which flows past the Station. The estimated cost at the time of the letter was 17,000 pound with an annual running cost of 1,866. Pound.

Details of the transmission lines to Higaturu, Sangara Mission and the Sangara Rubber Estate and sub stations were explained. The estimated alternative cost of generating power with diesel is detailed as a comparison. One letter mentions a time frame of five years for the completion of the power station.

There are no details available if any construction works had begun at the time of the eruption of Mt Lamington in January 1951.

Some of the Europeans in Higaturu

The Cowleys

Cecil and Amalya Cowley

Erl Cowley

Pamela Virtue

Cecil Francis Cowley was an employee of the Australian Administration of PNG and became the District Commissioner of the Northern Province in 1950. The district headquarters were located in the village of Higaturu, at the base of Mt Lamington.

In December of that year, Cecil’s children, Erl and Pamela, returned home from boarding school in Australia for the holidays. On January 15 the first signs of volcanic unrest began with smoke emerging from Mt Lamington.

Cecil Cowley, in contact with Port Moresby, sent reports of the eruption and requested a full-scale evacuation and the presence of a volcanologist. He suggested a plane could be sent to report on the eruption. Communications with Port Moresby were very difficult due to the radio static and there was some confusion as to exactly what was requested. There was later dispute whether Cowley had requested a volcanologist during this call but there was no doubt that he had.

Judge Phillips, the acting administrator, decided to visit Popondetta and meet with Cowley and flew there on the Friday. The Cowley’s went to Popondetta airfield expecting to see the volcanologist. Judge Phillips was not an expert on volcanos but had witnessed one such event at Rabaul.

During this time Mrs Cowley strongly expressed her concerns and suggested an immediate evacuation, but Judge Phillips believed it was unnecessary unless the volcano became violent. He advised her to go to Kokoda if the situation worsened.

District Commissioner Cowley lacked the desired volcanological expertise and was not able to order an evacuation. The acting administrator and senior officer in Port Moresby decided against evacuation, despite concerns expressed by those in the area.

Reverend Dennis Taylor, of Sangara Mission with his limited experience of a volcanic eruption, reassured the mission personnel. His reassurance aligned with Judge Phillips’ belief that there was no immediate cause for concern. Ultimately, the decision not to evacuate was primarily made by Judge Phillips and Reverend Taylor, with support from their subordinates.

Amalya Cowley had been having sleepless nights at Higaturu because of the threatening seismic and eruptive behaviour of Mount Lamington. She was encouraged by her husband to spend the night at Sangara Rubber Plantation a short distance from Higaturu, and she reluctantly agreed. She was comforted that her daughter Pamela would be accompanying her. Cecil drove them to Sangara on January 20 promising to see them the following morning.

Cecil Cowley returned to Higaturu to be with his son Erl. They perished with all others in Higaturu.

Amalya and daughter Pamela narrowly avoided death at Sangara.

Margaret de Bibra

In 1947, qualified teacher Margaret de Bibra arrived and founded the Martyrs Memorial School at Sangara village in Papua New Guinea’s Northern Province.

On Sunday 21st January De Bibra wrote:

We have a volcano! Just at our back door Mt Lamington lies behind us and

consists of four or five sugar-loaf peaks. We have always loved her for her beauty and nearness … [but now] she has changed from fairy queen to a wicked witch, and the gossamer scarves of mist [seen in the early mornings] have turned into smoky outpourings of some bubbling cauldron …

For days we had earth tremors; at first occasional ones such as we [had] experienced before, and then they became almost continuous and the face of Lamington became scarred with great patches of bare earth, caused by landslides. Then one morning—January 18th—after a night of continuous tremors, smoke appeared. At first there was only a little. Then it came pouring out in great thick puffs high into the sky, wreathing and curling in awe-inspiring cauliflower shapes …

***

What do the people think? We are carrying on our work as usual, though we run out from time to time to watch it …

The Papuans?—well, most are calm, many are apprehensive and some really frightened, especially those whose villages are near the mount. It is all understandable, in fact it is to their credit that there is no panic. Lamington has not been a volcano within the memory of living man, nor in the legend of the people. True, Lamington is feared as the home of spirits, and no local man—even Christian—will venture to the top. As

one of our Church Councillors said, ‘The mountain people do not understand. They are afraid. We understand a little and we are afraid too. Our fathers did not know of it. The trembling of the earth yes, but not the fire. At night it is like a torch and we do not understand the sign.’

What will it mean? … How will it affect the faith of new Christians? Can we make them understand what a volcano is, or will it be a return to old fears and superstition? … Will you think of the people here, particularly the Managalas people, and those near our stations of Sewa and Sehaperete [on the distant northeastern side of the mountain]? Pray for them and for us, that out of this good may come, and as the dead mount.came.to………… [the letter ends abruptly at this point].

Margaret de Bibra perished that morning.

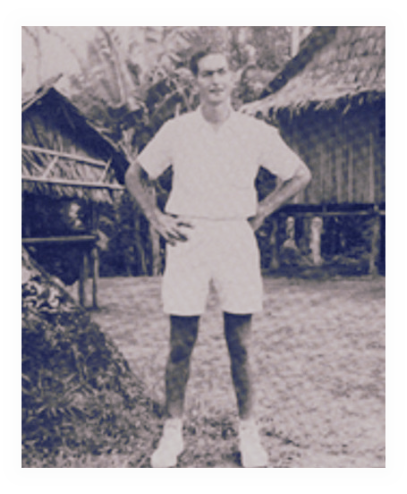

Kevin Woiwod

Kevin Woiwod was a young carpenter employed with the Department of Works and Housing.

He arrived in Higaturu in December 1950. Kevin possessed a strong passion for photography, and during his brief time in Higaturu, he managed to capture some unique shots of the District Headquarters. These photographs remain the only visual documentation of the facility. Additionally, he seized the opportunity to photograph the early stages of Mount Lamington’s volcanic eruption.

Recognizing the significance of his images, he promptly sent them to the Australian press. These photographs were transported on the final plane departing Popondetta before the volcano’s devastating eruption.

Tragically, Kevin Woiwod fell victim to the eruption, and his remains were never recovered.

On the morning of the cataclysmic event, witnesses observed a small group of men heading towards Mount Lamington. It is believed that Kevin was among them, driven by his desire to capture more photographs amidst the unfolding natural disaster.

Reverend Dennis Taylor

]n 1944, Reverend Dennis Taylor and his family were relocated from Wanigela to Sangara with the aim of reviving the Anglican mission. Over time, Higaturu and Sangara developed into twin settlements, serving as centers for both State and Church representatives in the district surrounding Mount Lamington.

During the resurgence of the Anglican Mission from 1945 to 1950, Reverend Dennis Taylor played a significant role in rebuilding the Sangara and Isivita stations. He utilised his skills as a bushman and his organizational abilities to repair St. James Church and establish a schoolroom. Reverend John Rautamara, a remarkable athlete and preacher, assisted Taylor at Sangara, ministering to the Orokaiva people.

On the evening of January 21st, 1951, Sister Pat Durdin at Isivita Mission observed a strange light in the sky and wondered if it was related to volcanic activity. As the volcano became more active with denser smoke resembling and a grey mass rising from the ground, people became terrified. Some sought refuge at the mission station, and Reverend Dennis Taylor visited to provide reassurance. Reverend Taylor’s confidence stemmed from his personal experience with the explosive eruption at Goropu in 1943-44 while stationed at Wanigela Mission. He believed that the current situation at Lamington was less severe, despite its intensity. He had previously shared this opinion with the Cowleys at Higaturu. Phillips and Taylor aimed to project knowledge and authority regarding volcanic eruptions based on their personal experiences at other volcanoes. Their intention was to maintain control over the volcanic crisis. Reverend Taylor arrived in Isivita accompanied by two local school teachers, George Ambo and Albert Maclaren Ririka. They had come to assist the mission staff in managing the growing number of people seeking reassurance and protection. Reverend Taylor later returned to Sangara Mission.

On Sunday morning, a climactic explosion occurred, causing a dark mass of ash to shoot up from the crater, reaching a height of 40,000 feet in just two minutes. The ash formed a large expanding mushroom-shaped summit, giving the impression that the entire countryside was erupting. While the European women from Sangara Plantation stayed at Popondetta with Mrs. Kleckham and Mrs. Morris, the European men demonstrated great determination by turning the truck around and driving back towards Sangara and Higaturu, despite the risks posed by the still active volcano. They were unaware of what further eruptions might occur or what they would encounter in the disaster zone. During their journey, they came across Reverend Dennis Taylor, who had been brought to a nearby location called Monge, or Maungi, by mission boys. Despite suffering severe burns all over his body, Reverend Taylor displayed incredible fortitude. He informed them that he had left his family at Sangara Mission and urged someone to assist them (Stephens 1953, 221). Reverend Taylor was transported back to Popondetta in the truck for medical attention. Urgent messages were dispatched to Sister Nancy Elliot at Gona Mission and Sister Jean Henderson at Eroro Mission, seeking medical supplies and aid. Sister Elliott, accompanied by Simon Peter Awado, undertook a foot journey to Popondetta. They arrived shortly after Reverend Taylor had passed away. The available morphine supply was distributed to those in the greatest need.

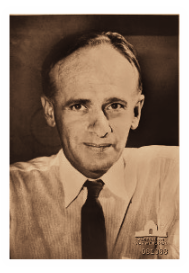

MR G. A. N. TAYLOR GC, Volcanologist

In late January 1951 local authorities in the northern district of Australian-administered Papua entered an alien landscape. The usual dense vegetation had been transformed into fields of burnt ash and destruction. The bodies of local people could be seen strewn across roads and huddled in destroyed buildings. They were the victims of an enormous volcanic blast at Mount Lamington, a long-dormant volcano that on 21 January 1951 destroyed vast swathes of land near the former Second World War battlefields of Buna, Gona, and Kokoda.

The blast sent a column of thick smoke and ash 15 kilometres into the air, and a superheated cloud of gas and volcanic particles racing at 100 kilometres an hour towards the village of Higaturu. Nearly 3,000 people are estimated to have lost their lives.

The blast triggered an enormous disaster relief response. Australian volcanologist George ‘Tony’ Taylor, who was working in nearby Rabaul at the time, arrived a day after the initial eruption and conducted surveys to assess the likelihood of further blasts. It was dangerous work: as he flew over the crater of the mountain his aircraft was at time struck by flying

rocks and debris. He frequently entered the ‘no-go’ area established around the volcano so that he could listen to and observe earth tremors.

He was later invested with a George Cross for his tireless efforts to help people and save lives in the aftermath.

Albert Speers

Albert Speers (1922-2014) was a remarkable individual dedicated to serving others and making a positive impact. Born in the New South Wales town of Goulburn, Australia, Speer joined the 2/2 Australian Field Ambulance and was stationed in New Guinea during World War II.

This marked the beginning of his deep connection with Papua New Guinea. After his demobilisation in May 1946, Speer joined the PNG Public Service as a medical assistant the following year.

Speer's unwavering commitment to helping others led him to various postings, including Kerema, Madang, and Saiho/Popondetta.

In the aftermath of the 1951 Mount Lamington eruption, Speer worked as a leader of the medical evacuation team. He worked tirelesslyto save lives and provide assistance to the affected population. His photographs of the volcano's aftermath can still be found in the National Library of Australia.

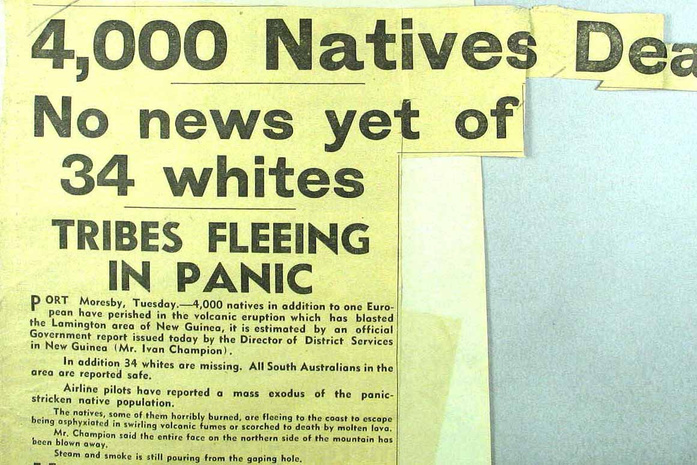

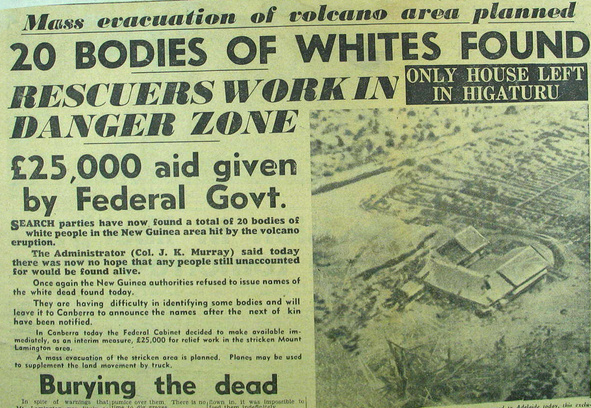

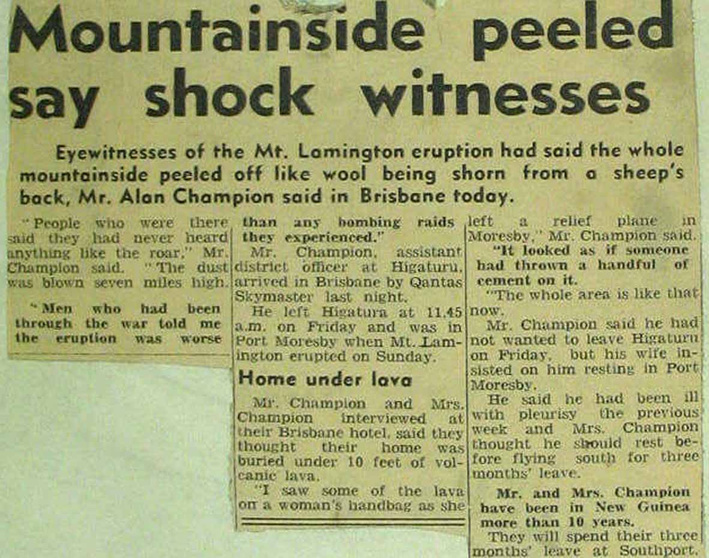

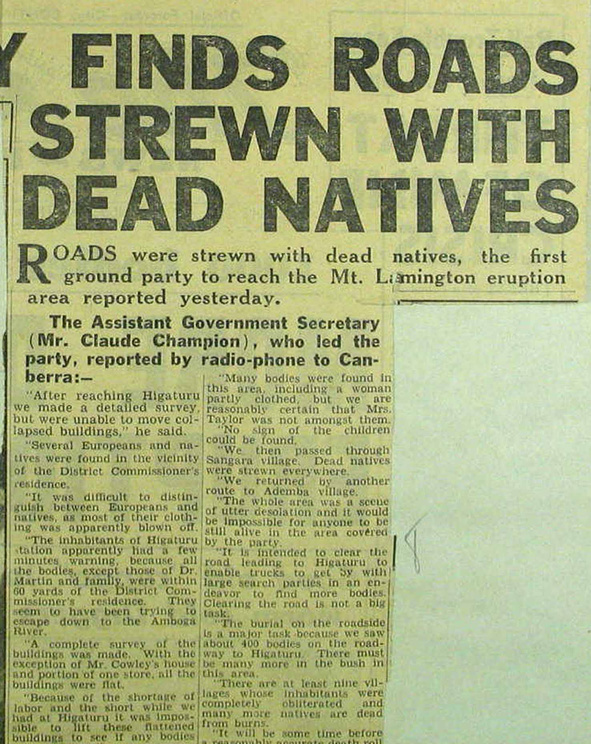

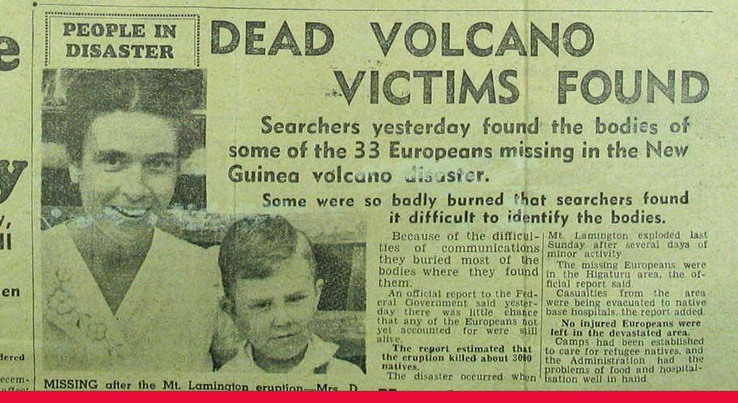

Newspaper Headlines About the Eruption

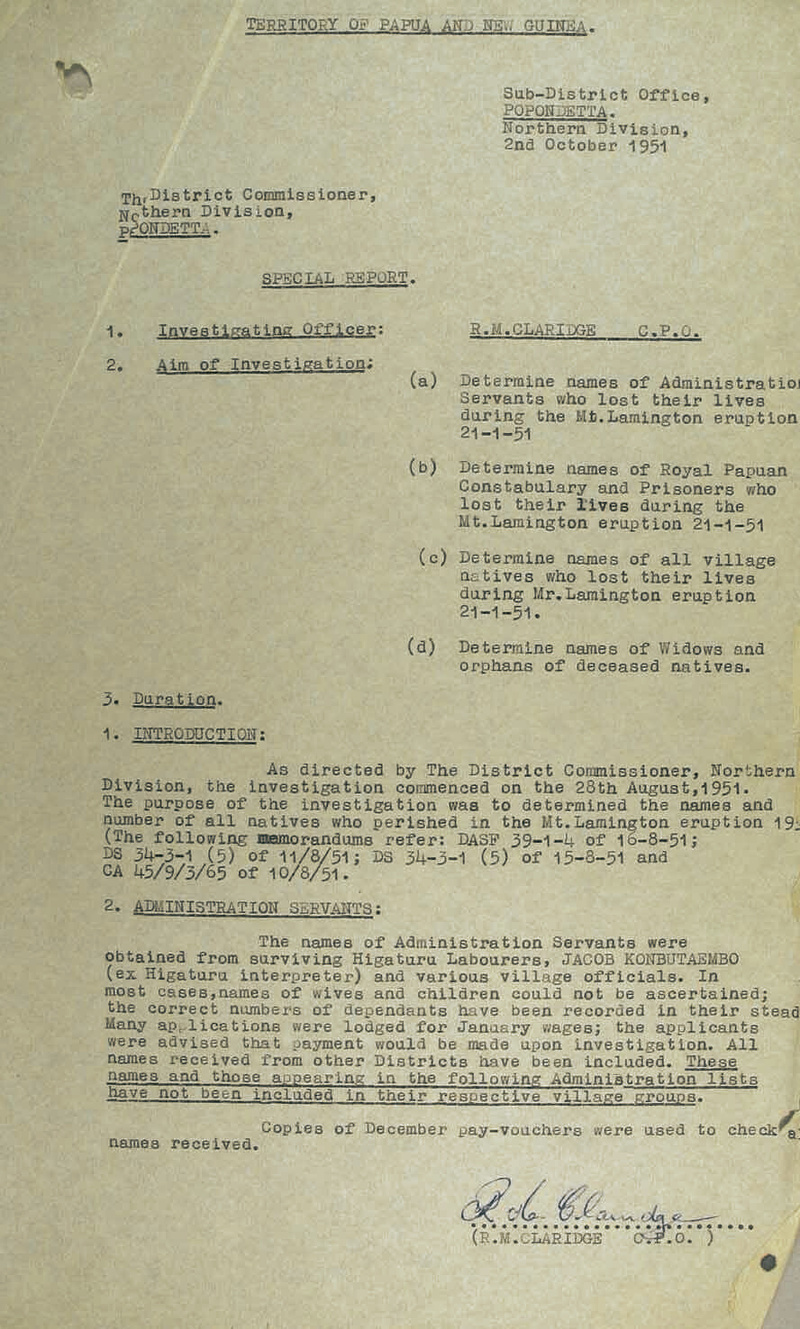

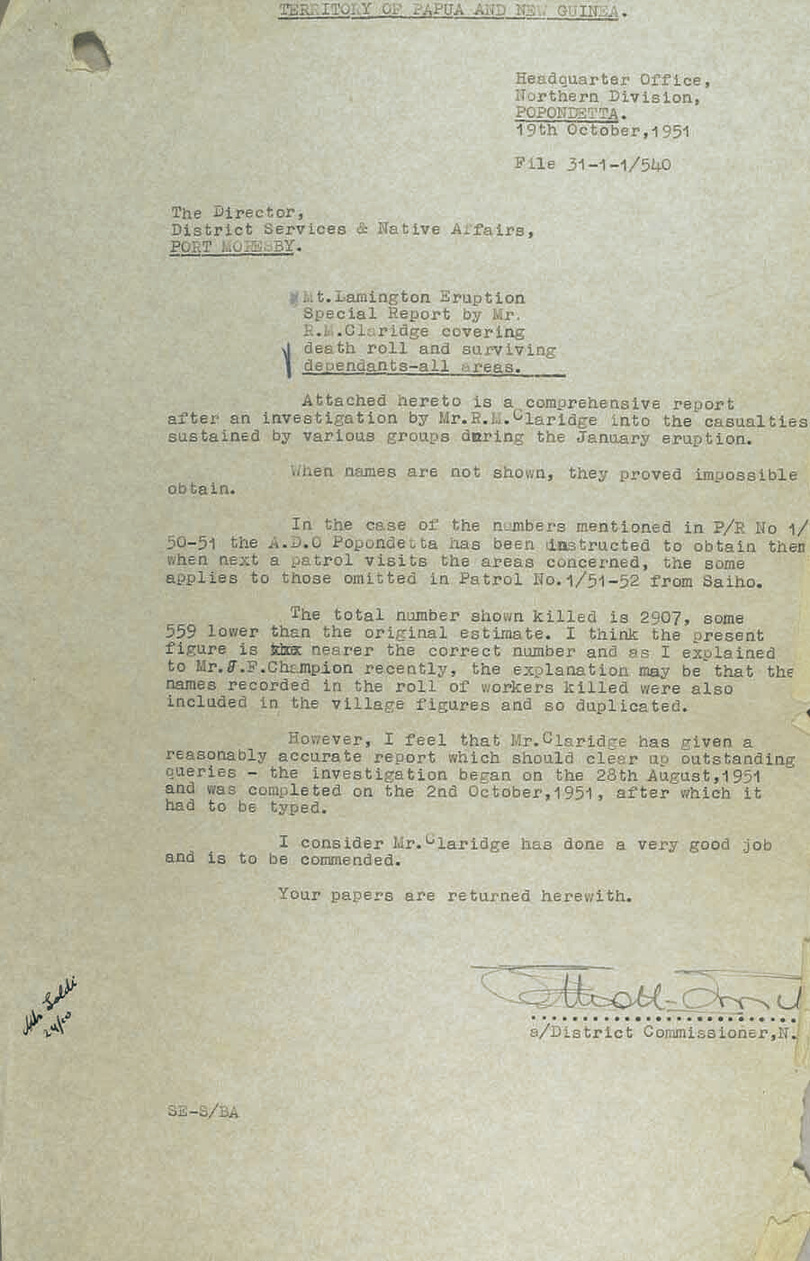

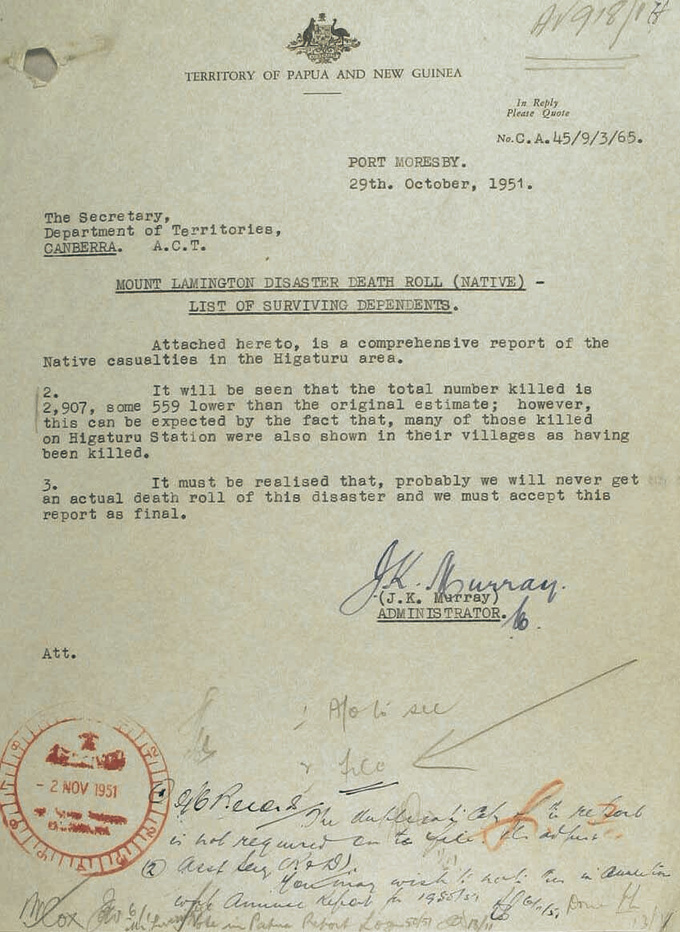

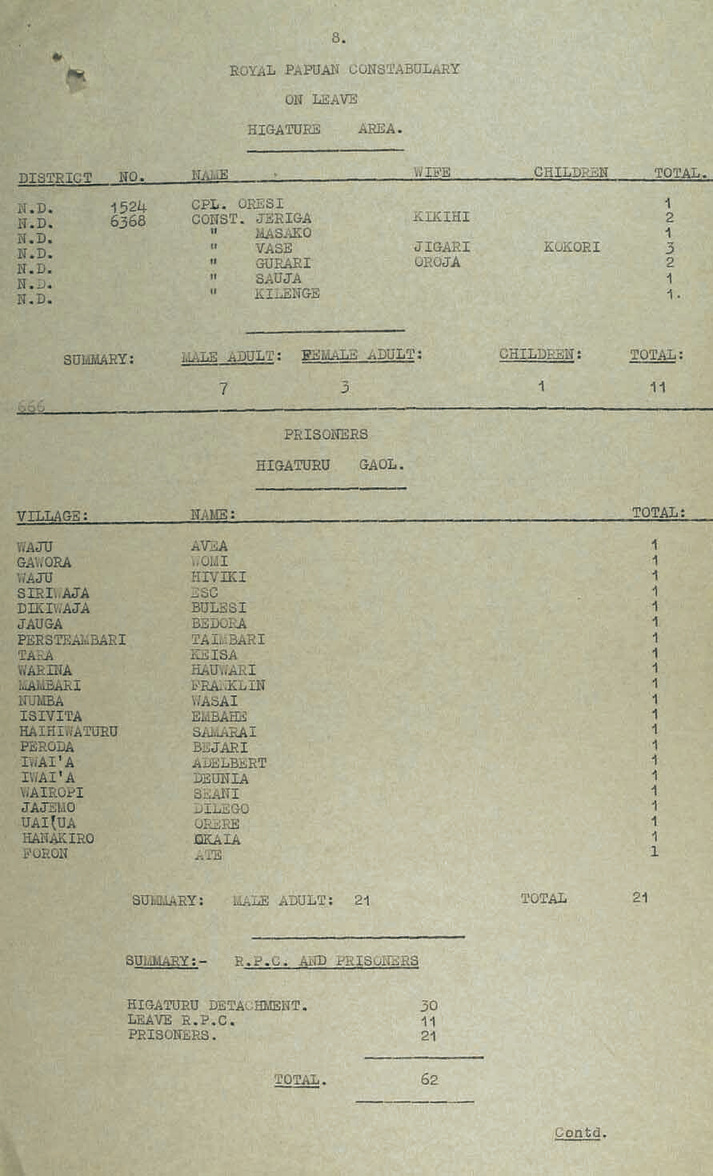

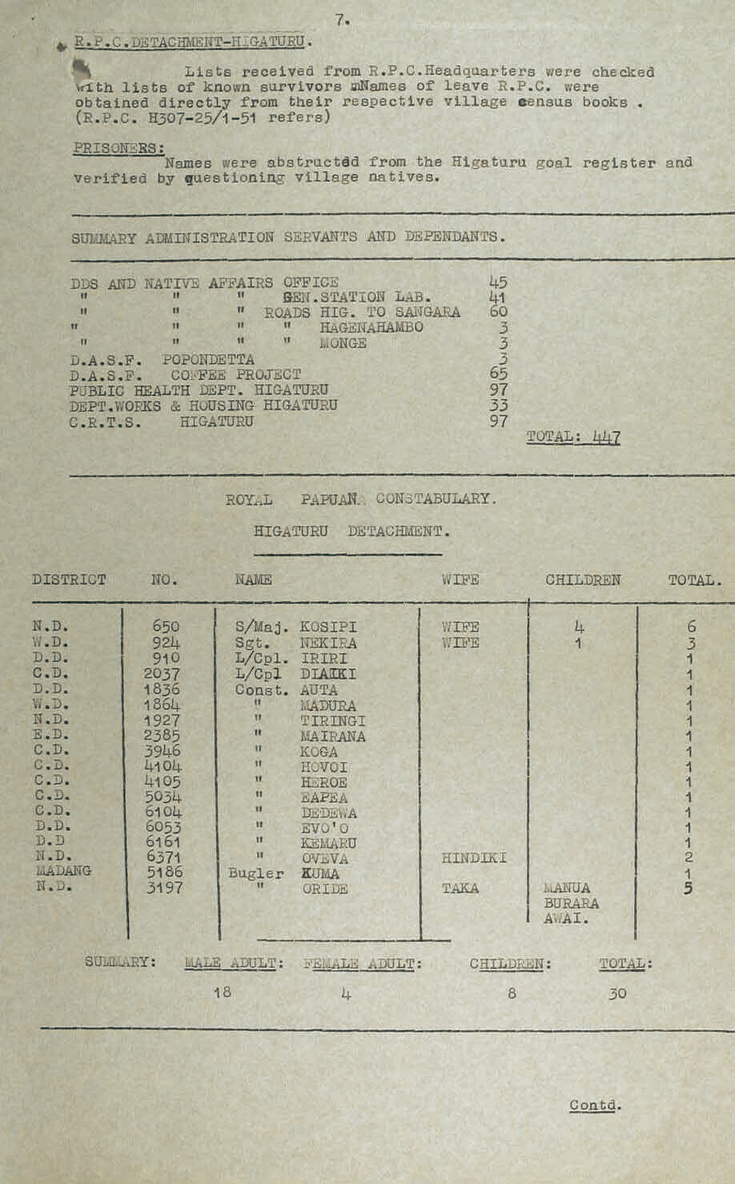

Official Death Reports

Acknowledgement

We’d like to acknowledge the work of R. Wally Johnson and his extensive research into the 1951 eruption. His work has guided much of the technical and geological accounts detailed above.

To the Oro Province survivors who generously shared their stories and firsthand accounts.

To Ross Bastiaan whose artistic talents brought the memory of Mount Lamington to life with the creation of this plaque.

And to Bernie Woiwod who embarked on an exhaustive process to create this lasting memorial to those killed, including his own brother, Kevin Woiwod.